Romsey and its Canal

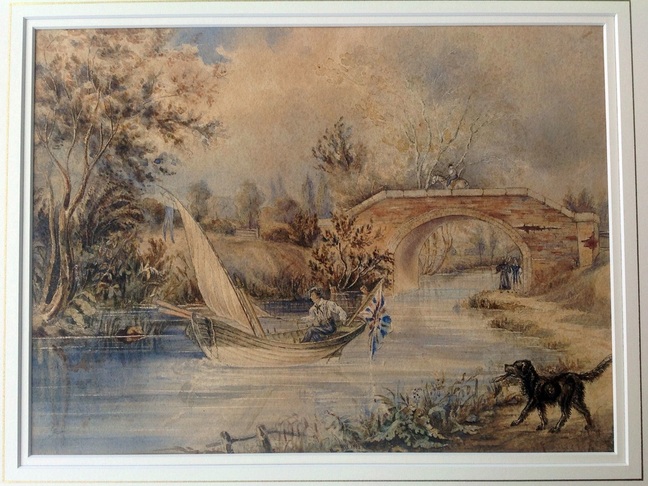

The above picture shows ‘Andover Canal below Rooksbury Mill’, which is in the southern part of Andover, north of the A303. It is displayed with the kind permission of Hampshire Cultural Trust.

Phoebe Merrick has very kindly supplied the following information on the history of the canal.

Foundation

Inland waterways have always offered an alternative to roads for the transport of goods and to a lesser extent people.

Some rivers are well suited for the purpose, others can be made use of with a certain amount of civil engineering, and others seem totally useless. The Test appears to fit into the latter category. There is no evidence that it was ever used as for navigation. From time to time it has been suggested that freight was brought up the river by water, such as stone for Romsey Abbey, but there is no definite evidence to support this hypothesis.

In the mid-17th century, the Itchen had been made navigable as far as Winchester and there were discussions to treat the Test similarly. [ 1666 Act for making divers Rivers navigable ] Despite further discussion and plans to hire a millwright to further the scheme, nothing was achieved.

A century later some prominent men of the Test Valley, particularly in Andover, re-activated the idea. In 1770 they had discussions with Robert Whitworth, the assistant of James Brindley, and came to the conclusion that the difficulties of rendering the Test navigable were such that it would be better to construct a canal.

The late 18th century was the hey-day of canal building and in the north of the county, Basingstoke had been connected to the River Wey and hence to the Thames network. Meanwhile, trade in Andover was declining and it was thought that a canal might re-vitalise it. In July 1788 a meeting was held at the Star and Garter in Andover and it was decided that a canal to the south coast was needed, with an upper cost limit of £35,000.

By February of 1789, Whitworth had produced a plan for the line of the canal and a bill was presented to Parliament by Andover’s two M.P.s. Amongst the supporters was the Earl of Portsmouth whose seat was at Hurstbourne Priors. Second on the list was John Poore of Redbridge, the tenant of Sir Charles Mill’s wharf at Redbridge, who stood to gain directly from a successful scheme. Most of the finance was provided by men from the north of Test Valley. Of the 350 shares issued, only two have been identified with Romsey.

Opposition came from millers in the Andover and Clatford area who feared that the canal would deprive them of the water they needed to drive their mill wheels. Winchester felt its trade might be adversely affected and also instructed their M.P.s to oppose the Andover Redbridge Canal Bill. The interests of various parties were protected by clauses in the bill. All of those claiming to need such protection were in Kings Somborne or north thereof.

Working Life

The bill was passed and the canal was constructed. It was 22 miles long. The original plan appears to show 21 locks, but later documents suggest that it had 24 locks fairly evenly spaced with wharves at Andover, Clatford, Fullerton, Stockbridge, Horsebridge, Mottisfont, Timsbury, Romsey and Redbridge. The canal construction was complete by 1794. The venture cannot be said to have been a financial success for the company never paid a dividend in the 65 years of its trading life.

The first barge to travel up the canal reached Clatford, just south of Andover, early in 1794. Clatford was the home of Tasker’s iron works and that company benefited from the canal. They could have iron shipped from South Wales to Redbridge, originally by sailing vessel, and then brought to their works by barge. In 1859 it cost them £1 10s [ £1.50 ] for six tons of material. The canal journey took two days, with an overnight stop in Romsey.

The canal’s existence is marked by advertisements. For example, the virtues of Stockbridge and its proximity to the canal appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle of 31 March 1794.

In 1804 a notice appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle advertising the lease of the whole concern at an auction sale to be held at the Star and Garter Inn in Andover. The notice stated that the ‘ Navigation on the Canal from Andover to Redbridge ’ was 23 miles long and consisted of several wharfs, dwelling-houses and store-houses at Andover, Stockbridge and Romsey. The advertisement was placed by R.A. Etwall, Clerk to the said Company and enquiries could be made of Mr New who was described as ‘the Inspector’.

A few other records survive including a couple of invoices for services issued by the company. One of these dated 1855 was sent to ‘ Mr Harris ’ charges for the delivery of 160 tons of chalk loaded at Sir J.B. Mills’ pit. This is the chalk quarry that is still beside the A3057 a little to the north of Timsbury. It was delivered to Redbridge at a cost of two shillings [10p] a ton. Another invoice of the same year was made out to ‘ Mr Guliver ’ for two loads of ‘ Small Chalk ’ at £2 per load, but no further detail is provided.

In March 1824 the Hampshire Chronicle had reported the theft of 3 sacks of wheat and two of barley from the Romsey wharf. The value of the grain is not known but a reward of ten guineas [£10.50] was offered. If the offenders were caught they were liable to be sentenced to death.

Amongst the folk-lore in the Romsey area, is one family’s account of a bride making her way from King’s Somborne to Romsey by barge, probably in the 1850s, and another family who claimed that their ancestors had used the canal for the transport of smuggled goods inland from Redbridge.

The census returns show that the canal provided work for some people in Romsey. In 1841, seven people were drawing their income from the canal. These include the wharfinger Joseph Lacey who was 40 at the time. He probably lived by the wharf which was south of Winchester Road where Southampton Road now runs. He lived there with his wife Elizabeth and four children. Ten years later, only one son, Charles, was still living at home. Since the canal closed three houses have been built in the vicinity of the former wharf. They back onto Harrage

The 1841 census also shows that Thomas Mitchell was a barge master living in Romsey in The Hundred. Martha Orman, (55) who lived at Toronto Cottage, Woodley, with her son Samuel, was a barge mistress. ( Toronto Cottage has not been identified .) John Pritchard (50), another barge master lived at Timsbury. In 1851 he described himself as a yeoman farmer. One of his sons, Edward kept the Malthouse at Timsbury, whereas two other sons, George and William, were described as ‘ labourer ’ and ‘ agricultural labourer ’.

The house next to the Malthouse is known as ‘ Barge House ’ to this day. In 1980, its then owner, John Glasspool, wrote that his grandfather had bought the house in 1925, then ‘ pretty dilapidated ’. The house still contained the manger where two horses were kept to pull barges on the canal. The building had contained accommodation for the ostlers who looked after these horses.

The 1841 census shows younger men as bargemen, namely John George (18), William Johnson (30), and Samuel Orman ( Martha’s 30 year old son ) is described as a barge labourer. By 1851 neither John George nor Samuel Orman were listed as working on the canal. William Johnson, a bargeman, continued to live in Love Lane and a new bargeman was the 26-year-old Joseph Stares who lived in the Cornmarket at The Dolphin Inn (now Bradbeers.) In Newton Lane, the family of John Withers was employed on the canal. John (52) was a bargeman, and his sons Clement (22), Stephen (20) and Frederick (14) were all described as barge drivers. Two other residents of Newton Lane also worked on the canal as barge drivers. They were John Somerton (42) and George Bungay (19).

Whereas some people remained in the employ of the canal company for years, others were employed on yearly contracts. For example Thomas Tarrant, described as being ‘ of Romsey Extra ’ but born at Foxcotte, Andover, came to Timsbury in 1801, after being pressed into the Navy for three years. He was hired for a year as a day labourer by Martin Effamy at a wage of ten guineas [ £10.50 ] plus board and lodging. He married a local girl and worked in the Romsey area for the next two years. He then went to Andover as a day labourer for Mr Thompson at the Wharf where he remained for three years, before returning to Romsey when he is said to have entered into a partnership with Martin Effamy. This arrangement lasted until the death of Mr Effamy after which the barge was given up.

The canal did not lead to a great upsurge of manufacturing along its length, if any at all. Traffic mostly consisted of heavy materials that would have been expensive to transport by land, such as the Caen stone used in the rebuilding of St Mary’s church in Andover in 1844. In 1859, 37,000 bricks for the building of an extension to Broadlands House were delivered by way of the canal.

It was stated that 2033 tons of goods had been transported in the year 1858. The major categories were:

Hides and bark 422 tons

Artificial manure 400 tons

Building materials, including slates 400 tons

Coals 300 tons

Timber 200 tons

Corn 166 tons

Soda 100 tons

It is interesting that no iron was included in this list, whereas in the early days of the canal, iron for Tasker’s works had been an important item, especially as it appears that iron was still being transported there in 1859. Perhaps it was also being transported by rail and road at this date, since the line from London to Andover was opened in 1854.

John Latham in his history of Romsey written early in the nineteenth century wrote

The vicinity to Southampton renders coal moderately cheap, it being brought there in shipping from Newcastle and other places, but the land carriage of eight miles makes it much dearer, for although it may be had through the medium of the navigable canal, which has been made from Southampton to Andover [ blank ] years since, this advantage cannot be made use of except for large quantities of perhaps twenty chaldrons,[1] brought in barges.

The first railway to come to Romsey ran from Bishopstoke (Eastleigh) to Milford (Salisbury) and was opened in 1847. Where it crossed the canal a bridge was constructed that was sufficiently high to allow working horses to walk underneath and that bridge is still there.

There is one small painting of the canal below Rooksbury Mill, Andover, which used to be on show in Andover library but otherwise there do not appear to be any paintings or sketches of the canal whatsoever.

The Southampton-Salisbury Canal

In 1795 an Act of Parliament was passed to enable a canal to be built between Southampton and Salisbury via Romsey and for part of its route use the Andover-Redbridge Canal. This canal started in Southampton near the Town Quay. Lower Canal Walk is a memorial to it. It crossed Southampton, where it has subsequently been a serious nuisance in the vicinity of the railway at Southampton Central station and along the coast line to the sea lock of the Andover-Redbridge canal. Barges used that canal as far as Kimbridge, crossing the Test by aqueduct. It followed the River Dun and then circled to the north of Dean Hill as far as a tunnel to West Grimstead. It proved impossible to retain the water in the section between there and Salisbury.

The original engineer was a Romsey man, Joseph Hill, whose work was inadequate. When in desperation, the shareholders called in another engineer, they employed the much more experienced engineer, John Rennie, who was scathing about the original efforts, including the poor quality of the bricks that had been used in the construction.

Some tolls were collected between 1803 and 1806 when lack of maintenance made the canal unusable.

An unidentified source has described the remains of this canal that were visible when the article was written[2]

Of the Southampton arm, very little visible evidence remains. The junction with the Andover Canal, beside Test Lane ½ mile north of the road bridge over the Test, was obliterated by the railway built in 1864. The course then headed for the ' present traffic roundabout at the top of Redbridge Road, blocks of flats having been built over it in recent years. It turned towards Red bridge Station; the wilderness in the garden of the station house is in fact the old canal. Towards Southampton Central Station the railway was constructed on or parallel to its course; a few years ago there used to be a length visible south of the line towards Redbridge Point, but this has now been filled in. The tunnel entrance was to the north of the railway tunnel; the length of the tunnel as constructed was 580 yard, and it ran beneath the present Civic Centre and Above Bar Street, emerging in the green known as the Hoglands. The canal divided after emerging into the light. Of the branch that made eastward to Northam, the coal depot on the Itchen, there seems to be no trace at all. The other branch ran south, parallel to Above Bar St and High St, and its course is denoted by Canal Walk and Lower Canal Walk. Two small mooring rings survive at the top of a flight of steps in Canal Walk, at the rear of Lankester's works; one wonders whether they were ever used, as it is not certain that the tunnel was at any time navigable throughout. This arm entered the river by the Gaol Tower. It used the ditch of the eastern wall of the old town for part of its course.

Of the Salisbury arm there is much more to be found. It left the Andover Canal 3½ miles north of Romsey; the junction is on the east side of A3057, between the 'Bear & Ragged Staff' and Mottisfont Station. The first few yards of the Salisbury arm are now a potato field, but the line of scrub and trees can be discerned heading westward, while the Andover ditch continues north. The minor road to Lockerley keeps close to the canal; part of this stretch has been filled by a stream, as can be seen opposite School Farm, just before you reach the village.

Fourteen locks were built on the Salisbury arm, presumably able to take boats 65ft. by 8ft 6in, the. same size as those on the Andover; most of them, however, have disappeared, though the sites of some are shown on 2½in OS maps as fords. There is no complete lock chamber left, though the bricks doubtless are still existing in various farm buildings and walls in the surrounding countryside. The most substantial lock remains are on the road from Lockerley Green to Holbury Wood ( SU 289269 ). On the west side of the first bridge you come to is a length of brick walling, about half of the south side of the lock. From here you can follow the bed of the canal to the site of the next lock, near the level-crossing on the road from Lockerley to East Dean.

The line of the canal continues through East and West Dean, being crossed and re-crossed by the railway to Salisbury. Some of the ninth lock can be found ( SU 246272 ) under a footbridge on a farm track on the north side of the West Dean—East Grimstead road, The width between the two portions of brickwork is about 14ft; 1½ miles farther on, by the church at E Grimstead, is the only well-preserved canal bridge surviving. It is brick-built, with a stepped parapet, and carries a farm road over the dry bed of the canal. Some yards west of the bridge, a stream joins the Salisbury arm, which continues mainly wet for the rest of its course.

The summit level is at Whaddon Common. Here the canal enters a cutting, which lies between the embankments of the Salisbury—Romsey Railway and the disused Salisbury & Dorset Junction line. On the south side of the latter embankment ( SU 195271 ) the cutting deepens and widens, so that from the high banks one gets the impression of a large, long lake formed by nature, with thickly-wooded banks. Here at least it would still be possible to put a boat on the Salisbury & Southampton Canal. But, as unfortunately only too often happens, the more accessible end of the cutting has been found a convenient dumping place for the disposal of old cars and other unwanted hardware, sinking slowly into the quagmire at the water's edge. The cutting can be reached from the track of the defunct Salisbury & Dorset line, or from one of the turnings on the north-east side of the A36, [ now Southampton Road, not A36 ] between Whaddon and Alderbury.

Whatever was built of the canal south of the main road has now been virtually obliterated; the line rounded Rectory Farm, but work must have been abandoned somewhere near Alderbury House. Tunnel Hill at Alderbury may have been where the tunnel on the descent to Salisbury was planned to be built, and in the woods north of W Grimstead is the summit reservoir of the canal.

The author cites the following references but without giving their dates of publication:

OS sheets 180 ( Southampton ), 168 ( Kimbridge—Lockerley Green ), 167 ( Salisbury )

"The Salisbury Canal--a Georgian Misadventure', by Hugh Braun, Wilts Arch & Nat Hist Mag, Vol 58, No 210

The Bankrupt Canal, by E. Welch (pub by City of Southampton)

The Canals of South & South East England, by Charles Hadfield

The End of the Canal

The canal had never been a success, although of some service in its day. By the 1850s it was clearly of only marginal usefulness and plans were made to replace it by a railway line.

The plan was to fill in the Canal and lay a railway line along its course. The Andover Canal Railway Company took over the operation of the canal and then had to prepare the route of the railway ready to submit the arrangements to Parliament where a private Act of Parliament would be needed. This was passed in 1860.

Apart from deciding on the route of the railway, where bridges would be needed, and where to locate stations, it was also necessary to make agreements with landowners who would be affected. In the Romsey area this particularly meant Lord Palmerston of Broadlands to the south of the town and Lord Sherborne in the Timsbury area.

Lord Palmerston arranged for the company to acquire land somewhat to the east of the canal and in exchange took the canal route through his land. As part of the arrangement the railway company was persuaded to re-route the main road between Romsey and Southampton away from Broadlands to the route of the current A3057/A27 along Mile Wall. The old turnpike road through Broadlands Park became a private track: it is used to this day for pedestrians going to the annual Romsey Show. Not only did the railway company bear much of the expense of altering the route of the main road, but also paid for the wall that runs alongside it, known locally as ‘Mile Wall’.

By contrast the settlement with Lord Sherborne was much simpler. His Lordship was anxious that his farming activities would not be obstructed by the railway and was guaranteed ‘proper level crossings … at all the points … where bridges over the Canal now exist’. The company was required to fill in the canal so that the land was level with its surroundings and to plant trees that shielded Timsbury Manor House from the railway line. Any land that had to be bought from Lord Sherborne for the construction of the railway would be priced at £100 per acre. This agreement was signed by George Hurst and Ralph Etwall, two of the provisional committee and by John Smith Burke, the engineer of the Andover Canal Railway Company.

Reports in the Romsey Register kept the population up to date with progress. The old canal bridge in Winchester Road (then called The Hundred and now Plaza roundabout) was removed in June 1862. Sadly no pictures of it have survived if ever made. By October of that year there were complaints of the muddy state of the road in the vicinity.

On 13 August 1863 the paper reported that ‘ The New line of the Railway to Redbridge is now staked out and will be proceeded with. It runs through a tract of very valuable land, and as, near Romsey, on will be raised on an embankment, it will not improve our local scenery.’

The stretch of canal between the estates of the two aristocratic landowners was not needed for the railway and was abandoned. In particular, for the stretch from the wharf beside Harrage northwards to Timsbury the canal survived with the water still in place. The outlet for the water was the Tadburn Lake which runs east-west along the twentieth century by-pass. The water goes underground by the Plaza but can be seen where it joins the stream at the junction of Southampton Road and the By-pass. At its northern end, it passes under Greatbridge Road and comes out on Linhay Meads, Timsbury. In the 1980s changes were made and the canal bed is now integrated into the River Test catchment management arrangements. After the removal of the locks, boards were inserted into the canal bed in a number of locations above Romsey to maintain the water level and improve its appearance. Latterly these have been removed for the benefit of fish movement, and the remains of the canal now more closely resemble a stream.

Sources

The author is grateful to the following writers for their work on the history of Romsey’s canals

Hampshire Chronicle 19 November 1804

John Glasspool letter to LTVAS Group 21 March 1980

63M48/55 Agreement between Andover Canal Railway Company and Lord Sherborne 31 Mar 1858 [Document held by Hampshire Record Office]

John Sims, ‘Lost Waterways: The Southampton and Salisbury’ (Canal Boat and Inland Waterways, April 2000) pp 46-7

The author has an excerpt from an unnamed book which is headed on each page ‘The South & South East’ It may be part of L.T.C. Rolt’s The inland waterways of England, (George Allen & Unwin, 1950)

Romsey Register passim (1862, 1863)

[1] A chaldron was a basket in which coal was sold. It usually contained about 26 hundredweight (cwt), compared with a ton which consists of 20 cwt.

[2] Despite extensive searches, it has not proved possible to identify this excellent source. It was probably written before 1963. If anyone can identify the book from which this is taken, please contact us.

The above picture shows ‘Andover Canal below Rooksbury Mill’, which is in the southern part of Andover, north of the A303. It is displayed with the kind permission of Hampshire Cultural Trust.

Phoebe Merrick has very kindly supplied the following information on the history of the canal.

Foundation

Inland waterways have always offered an alternative to roads for the transport of goods and to a lesser extent people.

Some rivers are well suited for the purpose, others can be made use of with a certain amount of civil engineering, and others seem totally useless. The Test appears to fit into the latter category. There is no evidence that it was ever used as for navigation. From time to time it has been suggested that freight was brought up the river by water, such as stone for Romsey Abbey, but there is no definite evidence to support this hypothesis.

In the mid-17th century, the Itchen had been made navigable as far as Winchester and there were discussions to treat the Test similarly. [ 1666 Act for making divers Rivers navigable ] Despite further discussion and plans to hire a millwright to further the scheme, nothing was achieved.

A century later some prominent men of the Test Valley, particularly in Andover, re-activated the idea. In 1770 they had discussions with Robert Whitworth, the assistant of James Brindley, and came to the conclusion that the difficulties of rendering the Test navigable were such that it would be better to construct a canal.

The late 18th century was the hey-day of canal building and in the north of the county, Basingstoke had been connected to the River Wey and hence to the Thames network. Meanwhile, trade in Andover was declining and it was thought that a canal might re-vitalise it. In July 1788 a meeting was held at the Star and Garter in Andover and it was decided that a canal to the south coast was needed, with an upper cost limit of £35,000.

By February of 1789, Whitworth had produced a plan for the line of the canal and a bill was presented to Parliament by Andover’s two M.P.s. Amongst the supporters was the Earl of Portsmouth whose seat was at Hurstbourne Priors. Second on the list was John Poore of Redbridge, the tenant of Sir Charles Mill’s wharf at Redbridge, who stood to gain directly from a successful scheme. Most of the finance was provided by men from the north of Test Valley. Of the 350 shares issued, only two have been identified with Romsey.

Opposition came from millers in the Andover and Clatford area who feared that the canal would deprive them of the water they needed to drive their mill wheels. Winchester felt its trade might be adversely affected and also instructed their M.P.s to oppose the Andover Redbridge Canal Bill. The interests of various parties were protected by clauses in the bill. All of those claiming to need such protection were in Kings Somborne or north thereof.

Working Life

The bill was passed and the canal was constructed. It was 22 miles long. The original plan appears to show 21 locks, but later documents suggest that it had 24 locks fairly evenly spaced with wharves at Andover, Clatford, Fullerton, Stockbridge, Horsebridge, Mottisfont, Timsbury, Romsey and Redbridge. The canal construction was complete by 1794. The venture cannot be said to have been a financial success for the company never paid a dividend in the 65 years of its trading life.

The first barge to travel up the canal reached Clatford, just south of Andover, early in 1794. Clatford was the home of Tasker’s iron works and that company benefited from the canal. They could have iron shipped from South Wales to Redbridge, originally by sailing vessel, and then brought to their works by barge. In 1859 it cost them £1 10s [ £1.50 ] for six tons of material. The canal journey took two days, with an overnight stop in Romsey.

The canal’s existence is marked by advertisements. For example, the virtues of Stockbridge and its proximity to the canal appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle of 31 March 1794.

In 1804 a notice appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle advertising the lease of the whole concern at an auction sale to be held at the Star and Garter Inn in Andover. The notice stated that the ‘ Navigation on the Canal from Andover to Redbridge ’ was 23 miles long and consisted of several wharfs, dwelling-houses and store-houses at Andover, Stockbridge and Romsey. The advertisement was placed by R.A. Etwall, Clerk to the said Company and enquiries could be made of Mr New who was described as ‘the Inspector’.

A few other records survive including a couple of invoices for services issued by the company. One of these dated 1855 was sent to ‘ Mr Harris ’ charges for the delivery of 160 tons of chalk loaded at Sir J.B. Mills’ pit. This is the chalk quarry that is still beside the A3057 a little to the north of Timsbury. It was delivered to Redbridge at a cost of two shillings [10p] a ton. Another invoice of the same year was made out to ‘ Mr Guliver ’ for two loads of ‘ Small Chalk ’ at £2 per load, but no further detail is provided.

In March 1824 the Hampshire Chronicle had reported the theft of 3 sacks of wheat and two of barley from the Romsey wharf. The value of the grain is not known but a reward of ten guineas [£10.50] was offered. If the offenders were caught they were liable to be sentenced to death.

Amongst the folk-lore in the Romsey area, is one family’s account of a bride making her way from King’s Somborne to Romsey by barge, probably in the 1850s, and another family who claimed that their ancestors had used the canal for the transport of smuggled goods inland from Redbridge.

The census returns show that the canal provided work for some people in Romsey. In 1841, seven people were drawing their income from the canal. These include the wharfinger Joseph Lacey who was 40 at the time. He probably lived by the wharf which was south of Winchester Road where Southampton Road now runs. He lived there with his wife Elizabeth and four children. Ten years later, only one son, Charles, was still living at home. Since the canal closed three houses have been built in the vicinity of the former wharf. They back onto Harrage

The 1841 census also shows that Thomas Mitchell was a barge master living in Romsey in The Hundred. Martha Orman, (55) who lived at Toronto Cottage, Woodley, with her son Samuel, was a barge mistress. ( Toronto Cottage has not been identified .) John Pritchard (50), another barge master lived at Timsbury. In 1851 he described himself as a yeoman farmer. One of his sons, Edward kept the Malthouse at Timsbury, whereas two other sons, George and William, were described as ‘ labourer ’ and ‘ agricultural labourer ’.

The house next to the Malthouse is known as ‘ Barge House ’ to this day. In 1980, its then owner, John Glasspool, wrote that his grandfather had bought the house in 1925, then ‘ pretty dilapidated ’. The house still contained the manger where two horses were kept to pull barges on the canal. The building had contained accommodation for the ostlers who looked after these horses.

The 1841 census shows younger men as bargemen, namely John George (18), William Johnson (30), and Samuel Orman ( Martha’s 30 year old son ) is described as a barge labourer. By 1851 neither John George nor Samuel Orman were listed as working on the canal. William Johnson, a bargeman, continued to live in Love Lane and a new bargeman was the 26-year-old Joseph Stares who lived in the Cornmarket at The Dolphin Inn (now Bradbeers.) In Newton Lane, the family of John Withers was employed on the canal. John (52) was a bargeman, and his sons Clement (22), Stephen (20) and Frederick (14) were all described as barge drivers. Two other residents of Newton Lane also worked on the canal as barge drivers. They were John Somerton (42) and George Bungay (19).

Whereas some people remained in the employ of the canal company for years, others were employed on yearly contracts. For example Thomas Tarrant, described as being ‘ of Romsey Extra ’ but born at Foxcotte, Andover, came to Timsbury in 1801, after being pressed into the Navy for three years. He was hired for a year as a day labourer by Martin Effamy at a wage of ten guineas [ £10.50 ] plus board and lodging. He married a local girl and worked in the Romsey area for the next two years. He then went to Andover as a day labourer for Mr Thompson at the Wharf where he remained for three years, before returning to Romsey when he is said to have entered into a partnership with Martin Effamy. This arrangement lasted until the death of Mr Effamy after which the barge was given up.

The canal did not lead to a great upsurge of manufacturing along its length, if any at all. Traffic mostly consisted of heavy materials that would have been expensive to transport by land, such as the Caen stone used in the rebuilding of St Mary’s church in Andover in 1844. In 1859, 37,000 bricks for the building of an extension to Broadlands House were delivered by way of the canal.

It was stated that 2033 tons of goods had been transported in the year 1858. The major categories were:

Hides and bark 422 tons

Artificial manure 400 tons

Building materials, including slates 400 tons

Coals 300 tons

Timber 200 tons

Corn 166 tons

Soda 100 tons

It is interesting that no iron was included in this list, whereas in the early days of the canal, iron for Tasker’s works had been an important item, especially as it appears that iron was still being transported there in 1859. Perhaps it was also being transported by rail and road at this date, since the line from London to Andover was opened in 1854.

John Latham in his history of Romsey written early in the nineteenth century wrote

The vicinity to Southampton renders coal moderately cheap, it being brought there in shipping from Newcastle and other places, but the land carriage of eight miles makes it much dearer, for although it may be had through the medium of the navigable canal, which has been made from Southampton to Andover [ blank ] years since, this advantage cannot be made use of except for large quantities of perhaps twenty chaldrons,[1] brought in barges.

The first railway to come to Romsey ran from Bishopstoke (Eastleigh) to Milford (Salisbury) and was opened in 1847. Where it crossed the canal a bridge was constructed that was sufficiently high to allow working horses to walk underneath and that bridge is still there.

There is one small painting of the canal below Rooksbury Mill, Andover, which used to be on show in Andover library but otherwise there do not appear to be any paintings or sketches of the canal whatsoever.

The Southampton-Salisbury Canal

In 1795 an Act of Parliament was passed to enable a canal to be built between Southampton and Salisbury via Romsey and for part of its route use the Andover-Redbridge Canal. This canal started in Southampton near the Town Quay. Lower Canal Walk is a memorial to it. It crossed Southampton, where it has subsequently been a serious nuisance in the vicinity of the railway at Southampton Central station and along the coast line to the sea lock of the Andover-Redbridge canal. Barges used that canal as far as Kimbridge, crossing the Test by aqueduct. It followed the River Dun and then circled to the north of Dean Hill as far as a tunnel to West Grimstead. It proved impossible to retain the water in the section between there and Salisbury.

The original engineer was a Romsey man, Joseph Hill, whose work was inadequate. When in desperation, the shareholders called in another engineer, they employed the much more experienced engineer, John Rennie, who was scathing about the original efforts, including the poor quality of the bricks that had been used in the construction.

Some tolls were collected between 1803 and 1806 when lack of maintenance made the canal unusable.

An unidentified source has described the remains of this canal that were visible when the article was written[2]

Of the Southampton arm, very little visible evidence remains. The junction with the Andover Canal, beside Test Lane ½ mile north of the road bridge over the Test, was obliterated by the railway built in 1864. The course then headed for the ' present traffic roundabout at the top of Redbridge Road, blocks of flats having been built over it in recent years. It turned towards Red bridge Station; the wilderness in the garden of the station house is in fact the old canal. Towards Southampton Central Station the railway was constructed on or parallel to its course; a few years ago there used to be a length visible south of the line towards Redbridge Point, but this has now been filled in. The tunnel entrance was to the north of the railway tunnel; the length of the tunnel as constructed was 580 yard, and it ran beneath the present Civic Centre and Above Bar Street, emerging in the green known as the Hoglands. The canal divided after emerging into the light. Of the branch that made eastward to Northam, the coal depot on the Itchen, there seems to be no trace at all. The other branch ran south, parallel to Above Bar St and High St, and its course is denoted by Canal Walk and Lower Canal Walk. Two small mooring rings survive at the top of a flight of steps in Canal Walk, at the rear of Lankester's works; one wonders whether they were ever used, as it is not certain that the tunnel was at any time navigable throughout. This arm entered the river by the Gaol Tower. It used the ditch of the eastern wall of the old town for part of its course.

Of the Salisbury arm there is much more to be found. It left the Andover Canal 3½ miles north of Romsey; the junction is on the east side of A3057, between the 'Bear & Ragged Staff' and Mottisfont Station. The first few yards of the Salisbury arm are now a potato field, but the line of scrub and trees can be discerned heading westward, while the Andover ditch continues north. The minor road to Lockerley keeps close to the canal; part of this stretch has been filled by a stream, as can be seen opposite School Farm, just before you reach the village.

Fourteen locks were built on the Salisbury arm, presumably able to take boats 65ft. by 8ft 6in, the. same size as those on the Andover; most of them, however, have disappeared, though the sites of some are shown on 2½in OS maps as fords. There is no complete lock chamber left, though the bricks doubtless are still existing in various farm buildings and walls in the surrounding countryside. The most substantial lock remains are on the road from Lockerley Green to Holbury Wood ( SU 289269 ). On the west side of the first bridge you come to is a length of brick walling, about half of the south side of the lock. From here you can follow the bed of the canal to the site of the next lock, near the level-crossing on the road from Lockerley to East Dean.

The line of the canal continues through East and West Dean, being crossed and re-crossed by the railway to Salisbury. Some of the ninth lock can be found ( SU 246272 ) under a footbridge on a farm track on the north side of the West Dean—East Grimstead road, The width between the two portions of brickwork is about 14ft; 1½ miles farther on, by the church at E Grimstead, is the only well-preserved canal bridge surviving. It is brick-built, with a stepped parapet, and carries a farm road over the dry bed of the canal. Some yards west of the bridge, a stream joins the Salisbury arm, which continues mainly wet for the rest of its course.

The summit level is at Whaddon Common. Here the canal enters a cutting, which lies between the embankments of the Salisbury—Romsey Railway and the disused Salisbury & Dorset Junction line. On the south side of the latter embankment ( SU 195271 ) the cutting deepens and widens, so that from the high banks one gets the impression of a large, long lake formed by nature, with thickly-wooded banks. Here at least it would still be possible to put a boat on the Salisbury & Southampton Canal. But, as unfortunately only too often happens, the more accessible end of the cutting has been found a convenient dumping place for the disposal of old cars and other unwanted hardware, sinking slowly into the quagmire at the water's edge. The cutting can be reached from the track of the defunct Salisbury & Dorset line, or from one of the turnings on the north-east side of the A36, [ now Southampton Road, not A36 ] between Whaddon and Alderbury.

Whatever was built of the canal south of the main road has now been virtually obliterated; the line rounded Rectory Farm, but work must have been abandoned somewhere near Alderbury House. Tunnel Hill at Alderbury may have been where the tunnel on the descent to Salisbury was planned to be built, and in the woods north of W Grimstead is the summit reservoir of the canal.

The author cites the following references but without giving their dates of publication:

OS sheets 180 ( Southampton ), 168 ( Kimbridge—Lockerley Green ), 167 ( Salisbury )

"The Salisbury Canal--a Georgian Misadventure', by Hugh Braun, Wilts Arch & Nat Hist Mag, Vol 58, No 210

The Bankrupt Canal, by E. Welch (pub by City of Southampton)

The Canals of South & South East England, by Charles Hadfield

The End of the Canal

The canal had never been a success, although of some service in its day. By the 1850s it was clearly of only marginal usefulness and plans were made to replace it by a railway line.

The plan was to fill in the Canal and lay a railway line along its course. The Andover Canal Railway Company took over the operation of the canal and then had to prepare the route of the railway ready to submit the arrangements to Parliament where a private Act of Parliament would be needed. This was passed in 1860.

Apart from deciding on the route of the railway, where bridges would be needed, and where to locate stations, it was also necessary to make agreements with landowners who would be affected. In the Romsey area this particularly meant Lord Palmerston of Broadlands to the south of the town and Lord Sherborne in the Timsbury area.

Lord Palmerston arranged for the company to acquire land somewhat to the east of the canal and in exchange took the canal route through his land. As part of the arrangement the railway company was persuaded to re-route the main road between Romsey and Southampton away from Broadlands to the route of the current A3057/A27 along Mile Wall. The old turnpike road through Broadlands Park became a private track: it is used to this day for pedestrians going to the annual Romsey Show. Not only did the railway company bear much of the expense of altering the route of the main road, but also paid for the wall that runs alongside it, known locally as ‘Mile Wall’.

By contrast the settlement with Lord Sherborne was much simpler. His Lordship was anxious that his farming activities would not be obstructed by the railway and was guaranteed ‘proper level crossings … at all the points … where bridges over the Canal now exist’. The company was required to fill in the canal so that the land was level with its surroundings and to plant trees that shielded Timsbury Manor House from the railway line. Any land that had to be bought from Lord Sherborne for the construction of the railway would be priced at £100 per acre. This agreement was signed by George Hurst and Ralph Etwall, two of the provisional committee and by John Smith Burke, the engineer of the Andover Canal Railway Company.

Reports in the Romsey Register kept the population up to date with progress. The old canal bridge in Winchester Road (then called The Hundred and now Plaza roundabout) was removed in June 1862. Sadly no pictures of it have survived if ever made. By October of that year there were complaints of the muddy state of the road in the vicinity.

On 13 August 1863 the paper reported that ‘ The New line of the Railway to Redbridge is now staked out and will be proceeded with. It runs through a tract of very valuable land, and as, near Romsey, on will be raised on an embankment, it will not improve our local scenery.’

The stretch of canal between the estates of the two aristocratic landowners was not needed for the railway and was abandoned. In particular, for the stretch from the wharf beside Harrage northwards to Timsbury the canal survived with the water still in place. The outlet for the water was the Tadburn Lake which runs east-west along the twentieth century by-pass. The water goes underground by the Plaza but can be seen where it joins the stream at the junction of Southampton Road and the By-pass. At its northern end, it passes under Greatbridge Road and comes out on Linhay Meads, Timsbury. In the 1980s changes were made and the canal bed is now integrated into the River Test catchment management arrangements. After the removal of the locks, boards were inserted into the canal bed in a number of locations above Romsey to maintain the water level and improve its appearance. Latterly these have been removed for the benefit of fish movement, and the remains of the canal now more closely resemble a stream.

Sources

The author is grateful to the following writers for their work on the history of Romsey’s canals

Hampshire Chronicle 19 November 1804

John Glasspool letter to LTVAS Group 21 March 1980

63M48/55 Agreement between Andover Canal Railway Company and Lord Sherborne 31 Mar 1858 [Document held by Hampshire Record Office]

John Sims, ‘Lost Waterways: The Southampton and Salisbury’ (Canal Boat and Inland Waterways, April 2000) pp 46-7

The author has an excerpt from an unnamed book which is headed on each page ‘The South & South East’ It may be part of L.T.C. Rolt’s The inland waterways of England, (George Allen & Unwin, 1950)

Romsey Register passim (1862, 1863)

[1] A chaldron was a basket in which coal was sold. It usually contained about 26 hundredweight (cwt), compared with a ton which consists of 20 cwt.

[2] Despite extensive searches, it has not proved possible to identify this excellent source. It was probably written before 1963. If anyone can identify the book from which this is taken, please contact us.